What is the PCC’s Research Impact Report?

In 2017, the PCC began an initiative to more deliberately track the impact of the research we fund. One of the mechanisms used for this is the RIR, or Research Impact Report.

The RIR is designed to highlight key areas in which PCC research is impactful, as well as areas in which additional resources may be necessary to bolster applied outcomes for the anti-doping community.

What does it measure?

The PCC chose three metrics to track:

- Research Outputs: Did any publications and/or presentations result from PCC funded research?

- Adoption: Are the results of the research now utilized within an anti-doping lab or outside of the industry?

- Spin Off Projects: Has the research resulted in any additional research funded by the PCC or another organization?

Researchers are also asked to describe the impact of their project on anti-doping in their own words, to ensure a holistic understanding of the project’s scope and contribution.

When do researchers receive the RIR?

The RIR was first sent in February 2017 to primary investigators with completed projects who were awarded funding from 2008-2015. For researchers with projects currently in progress, RIR responses will be solicited six months following the end of their project.

The delay is important, as research outputs are typically not in place immediately following project completion. While manuscripts and presentation abstracts may be planned, it may take a few months for acceptance by journals or conferences. Adoption can also be a lengthy process, especially within the context of WADA-Accredited laboratories, as interlaboratory precision is an important, often time consuming process. For these reasons, research impact can most accurately be reported at least six months to a year after completion – and in some cases longer. Researchers are always encouraged to keep the PCC informed of updates to their work to supplement formal reports.

What were the initial takeaways?

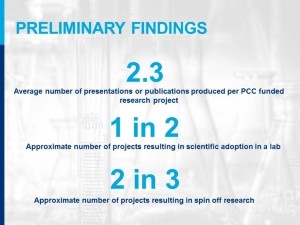

Preliminary RIR findings, first presented at the 2017 PCC Conference in April, were encouraging.

Of the 36 initial respondents, 26 had produced at least one research output as a result of their completed PCC funded project, or nearly 75%.

114 outputs total were reported, which is akin to slightly more than one output per project funded in the PCC’s history (not just those with data available, for which the ratio is more than 2:1).

Also encouraging, approximately 2 of 3 projects resulted in spin off projects, or research resulting from the success, or new questions produced by original projects.

What are the next steps?

Findings also provided necessary justification for the evolution of PCC programs and priorities. Adoption rates, while impressive, lagged behind other metrics. While the adoption rate for completed projects for which data is available averaged 50%, the PCC believes channeling additional resources to applying research results to real-world setting is critical to doping deterrence and detection efforts.

Realizing that adoption rates may be low for a multitude of reasons (including lack of time, connections, money, or specialized expertise on the part of researchers), the PCC developed the Translational Research Fund. This fund is designed to identify and support successful PCC research that would have a high level of impact on anti-doping if adopted. The fund may also be used for tech transfer, or the extrapolation of existing technologies to and from the anti-doping sphere. Three projects are already receiving funds from the Translational Research Fund.

For more information on the RIR or Translational Research Fund, please email Manager, Communications & Operations – Jocelyn Quiles at jquiles@cleancompetition.org.